As a kid I passed a lot of time in my own head. I went to a Quaker school for the first couple of grades where they would regularly gather us all for meeting and have us sit quietly. If the spirit moved you to speak you were encouraged to stand up and do so to the group. I would sit there and get lost in my own thoughts, but every so often someone would stand and speak out. It always felt like an unwelcome shock. But after we settled back into silence there would be a new kink in the path of my thinking and I usually enjoyed seeing where it led me.

Our driveway was an old gravel road half a mile long. After switching to a regular public school I would walk it each day and have a different kind of meeting experience. Either walking quietly with my brothers or alone. I’d feel the air and the light, smell the dirt and see the leaves rustle or hear snow and ice crunch. Nature and the environment around me filled in for the spirit in other people in keeping my thinking from going stale.

I love science fiction and thinking about the far future. Why are we here and where is it all headed? My favorite stories replace or extend the laws of the world we know and then play out the consequences. For example, Tower of Babylon and Exhalation by Ted Chiang both replace familiar rules and then play out where that leads. It’s easy to change rules at random, but I think it takes some genius to figure out how to change the rules so that an interesting story emerges from their faithful application.

Greg Egan is a science fiction author who extends or fills in between the laws we know. I cherish his work because it always makes me feel like I’m stretching my mind like dough. And because it convinces me that it is possible to at least imagine a future where humans keep learning but don’t use that as leverage to destroy themselves or the world around them.

“I keep asking myself, though: where do we go from here? History can’t guide us. Evolution can’t guide us. The C-Z charter says understand and respect the universe . . . but in what form? On what scale? With what kind of senses, what kind of minds? We can become anything at all — and that space of possible futures dwarfs the galaxy. Can we explore it without losing our way? Fleshers used to spin fantasies about aliens arriving to ‘conquer’ Earth, to steal their ‘precious’ physical resources, to wipe them out for fear of ‘competition’… as if a species capable of making the journey wouldn’t have had the power, or the wit, or the imagination, to rid itself of obsolete biological imperatives. Conquering the galaxy is what bacteria with spaceships would do — knowing no better, having no choice.” – Excerpt From Diaspora by Greg Egan

I was refreshing myself about von Neumann probes and came across a paper from Carl Sagan and William Newman called “The Solipsist Approach to Extraterrestrial Intelligence”. It makes the point that civilizations which develop sufficiently such that they can send out machines to dominate the universe might necessarily pick up a level of intelligence and maturity that they decide it is in their interest not to do so.

If scientific and technological progress actually leads inward towards a more empathic relationship to the universe I wonder what that means for the concept of a technological singularity. Maybe instead of the popularly discussed type of singularity that is loud like a bomb going off this one is more like ripples being lost among ocean waves? We learn how to fade into the background noise and just think and observe, staying in touch with the real world instead of sealing ourselves in bubbles of our own design until we go stale and cease to meaningfully live.

I enjoy imagining humanity heading in that direction. What could it look like along the way?

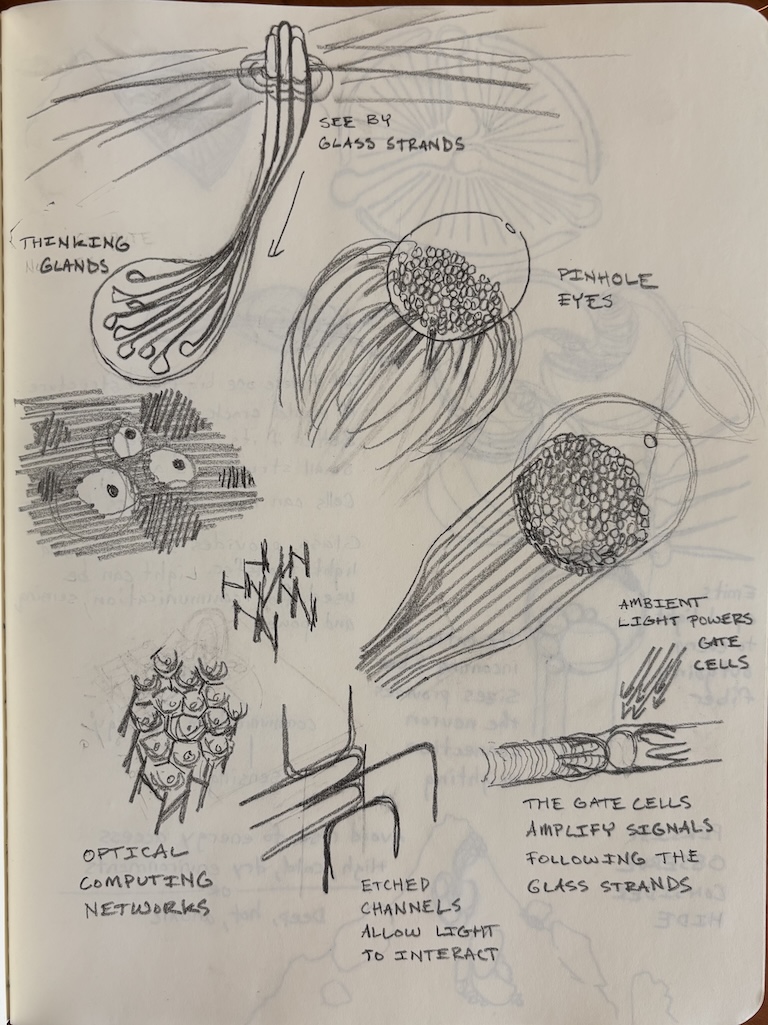

A surface like a comb in a bee hive made up of innumerable cells matted with light-bearing fibers. A faint glow resolves to a turbulent sea of superpositioned messages propagating cell-to-cell when slowed a million-fold. At the edges new cells mature and come online to add fresh computational safety margin for the substrate’s inhabitants. Damaged and dying cells are left high and dry, moving a shoreline in rule space separating the inner world from the outer one.

I spent a short fixed block of time during the summer of 2021 exploring building this concept. What is recounted here is much more a collection of a few experiments than a fleshed out implementation of anything.

The rough idea I had was to work out how to make a digital optical communication system in isolation without worrying about how it looked. In parallel I would come up with ways to map that design to a physical design that looked the way I wanted. Then I could try doing both parts for one cell. And later scale it up to a larger network. After that I’d figure out how to use the network to run some kind of distributed simulation that would let simple agents occupy an environment.

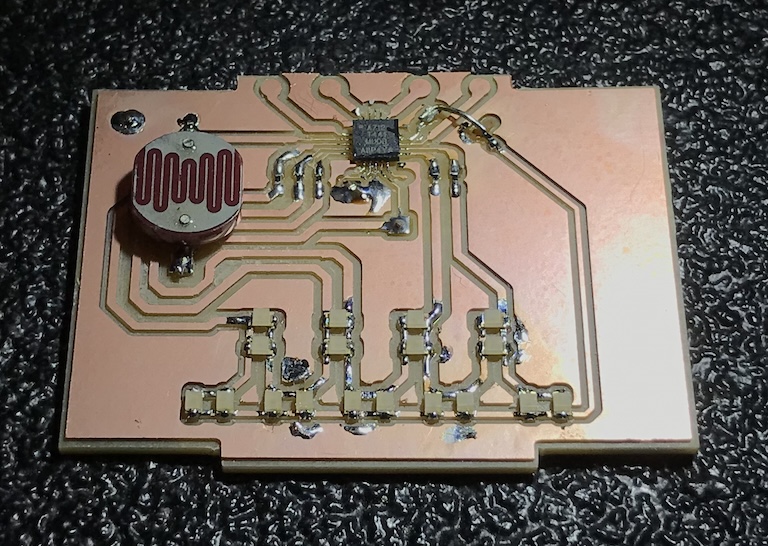

The optical communications network didn’t need to be efficient. It just needed to let messages be passed along and eventually reach their intended destination. I rummaged through my parts bins and decided that the walls of the cells would have LEDs for transmitting data and photoresistors for receiving it. Code running on an 8 bit ATtiny microcontroller would handle converting messages to and from pulses of light. I decided I would hand-wave away the details of this process at the beginning and just trust I’d be able to solve it somehow in software later.

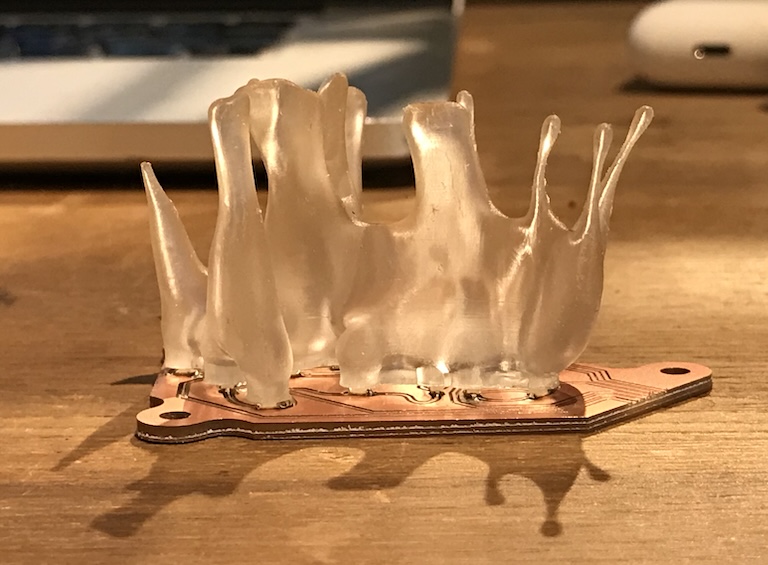

Light would be carried from the LEDs on one wall to the photodetectors on others via light guides which I would 3D print in resin. I had used this trick on some product development projects in the past so I knew it could work in principle.

I wanted the whole assembly to look like it was grown. Which would mean most parts would have to be unique even if they behaved the same. I didn’t want to design each cell by hand so I needed to come up with some sort of generative algorithm for each subsystem. There would be constraints in both directions, between the physical fame, the light guides, and the electronics. The electronics were going to be the most difficult part because no matter what I did to them I had to ensure they would still function afterwards. If the circuit was too complicated it wouldn’t be practical to achieve that. But if it was too simple it wouldn’t help sell the overall narrative of the artifact.

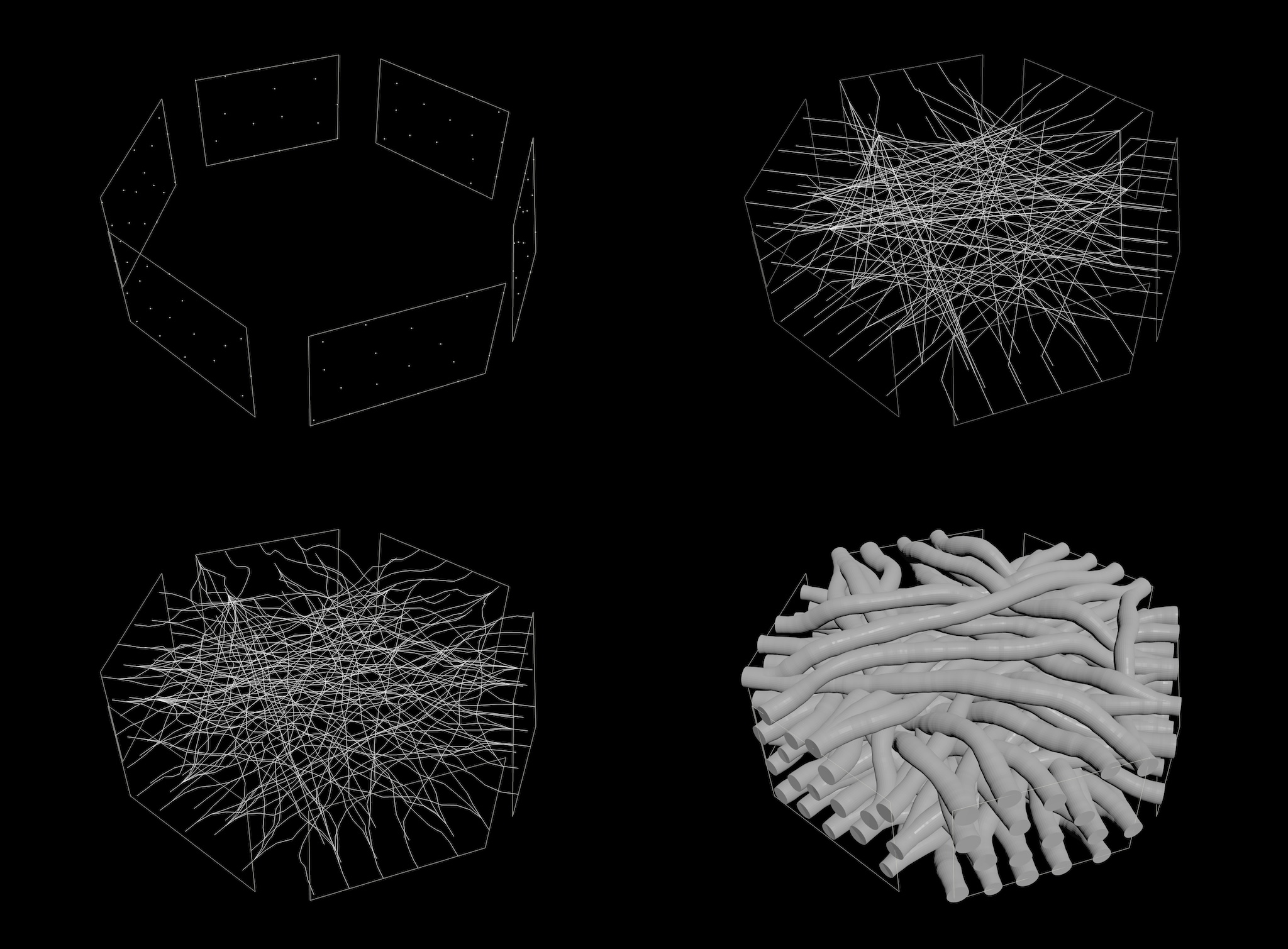

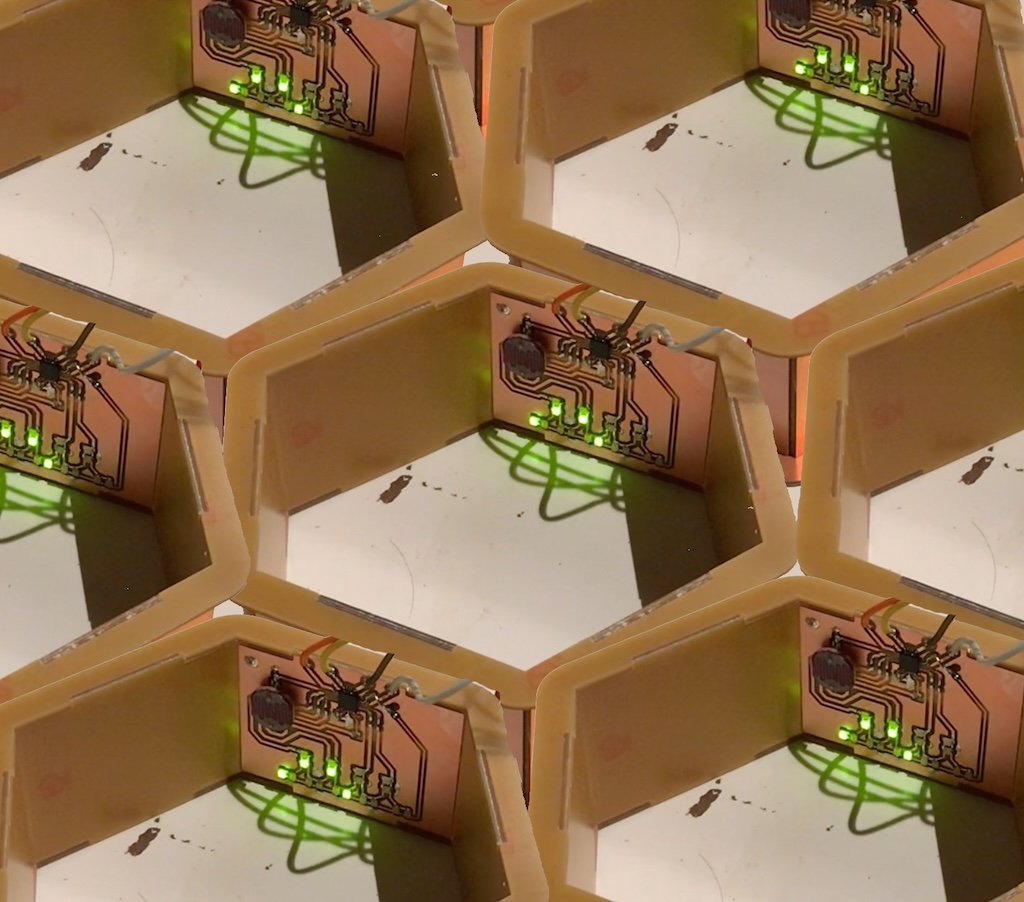

I settled on a specific scope- I’d start with a regular hexagonal grid for the frame. But the walls of each cell and the mat of 3D printed light guides in the center would be entirely unique per cell, created using a generative approach. I would define the electrical net for the computation and communications circuit and then just modify its layout generatively for the inner face of each cell wall. Then I would take the resulting locations of the LEDs and photodetectors as fixed constraints fed into the generation of a 3D model for the light guides to print.

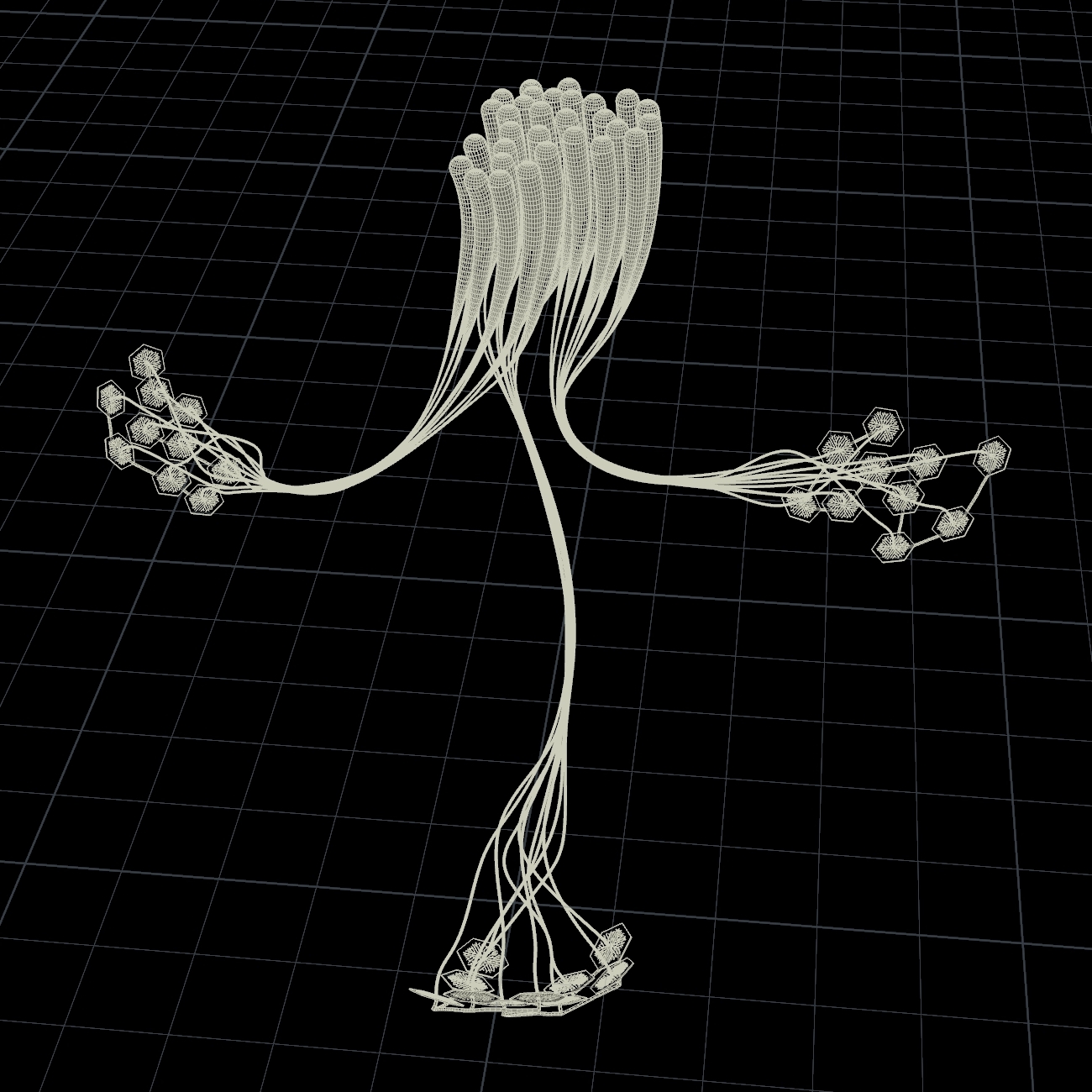

I worked backwards again by first working out a generative system for the light guides in SideFX Houdini. Input consisted of the points where the LEDs and photoresistors would be on each wall. Later these would be fed in from the result of whatever PCB generative system I came up with. For each LED I chose random photoresistors from the other walls and created a line from the LED to each of them. Then I set up a force-directed iterative solver which pushed them apart from each other (in a Solver node: resample -> apply force -> move).

Here’s an animation showing that iterative process. You can see it pushing the light guides apart but it’s not fully avoiding intersections between them. I was hoping this would be “good enough” and not compromise the optical communication too much. Maybe the unintentional cross channel mixing would need to be compensated for in software. Or those fibers could be left unused. Intersections were also structurally convenient- providing a way to hold the 3D print together for installation.

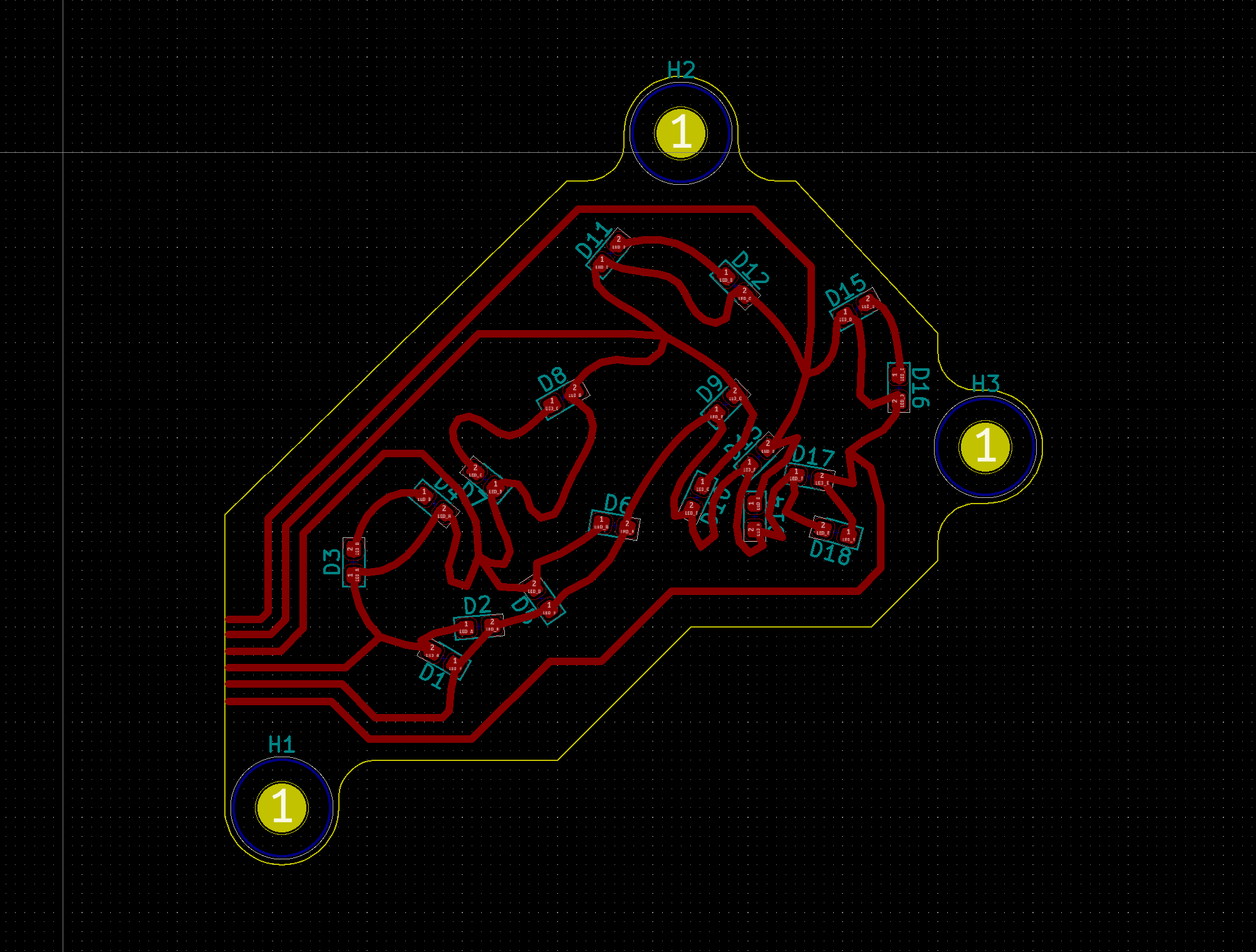

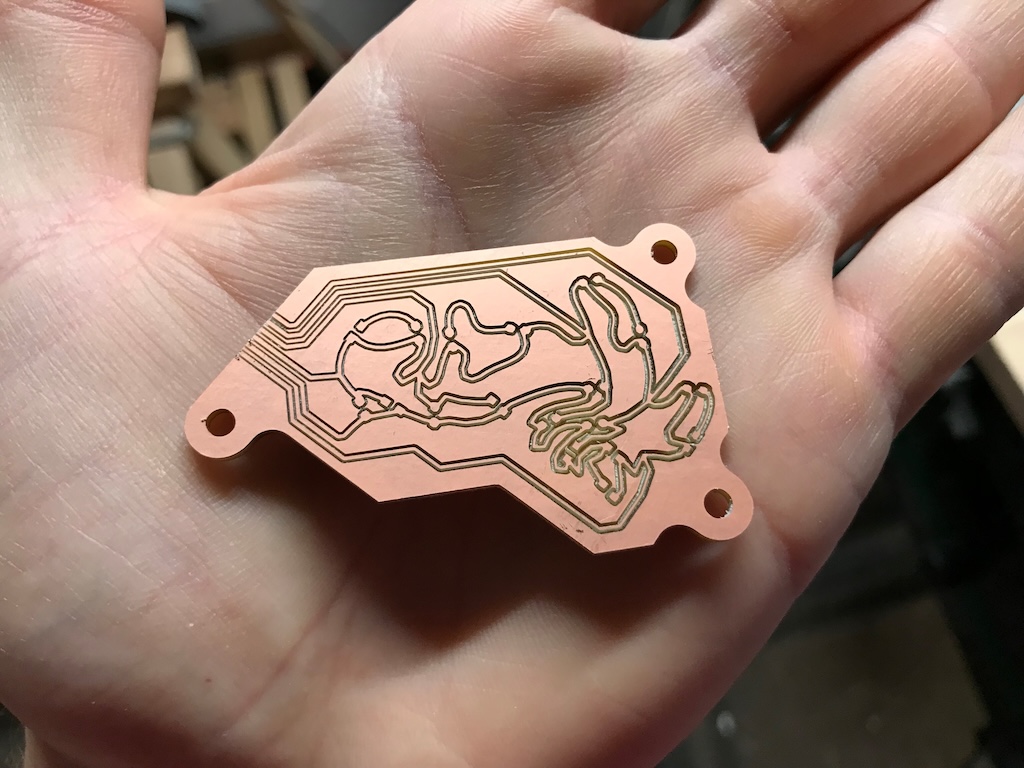

Getting back to the electronics I decided to work on the light emission part first. I wanted to have a single layer PCB design, which meant having a circuit topology which required no overlaps. I also wanted to maximize the number of LEDs that I could drive from the limited number of pins on the ATtiny. So I looked at Charlieplexing, which is a technique for driving lots of LEDs from few pins using the common ability of microcontroller pins to be in 3 different states: 1) high impedance input (disconnected) 2) driven to ground 3) driven to the system logic voltage. Full Charlieplexing wouldn’t have been possible with a 1 layer design so I pruned it until I had a 1 layer design which drove 18 LEDs from 6 I/O pins.

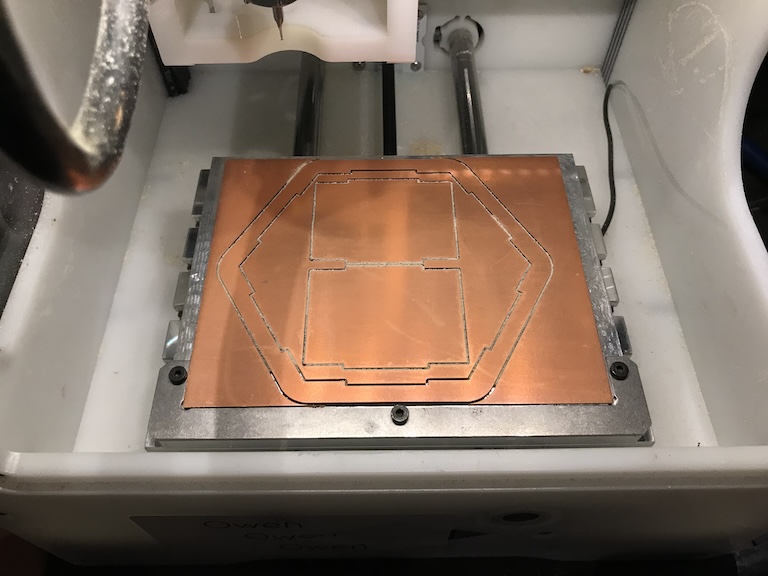

I designed a simple frame that I could also cut out on my Othermill from copper-clad FR1 and solder together.

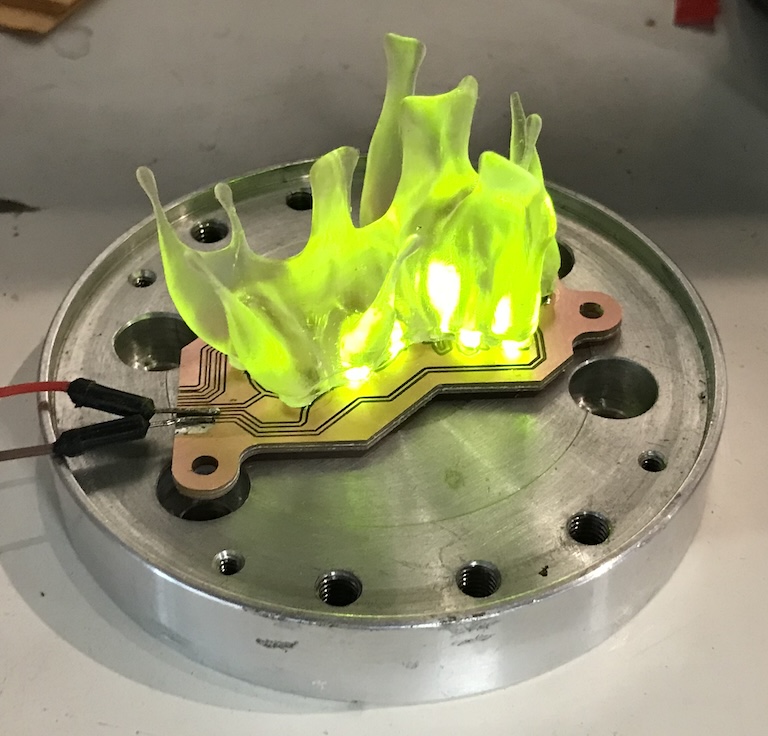

Soldered together and programmed with a simple pin state cycling program I got the proof of concept I was after. Now I had a basic working single layer PCB design which could programmatically control 18 LEDs. I could only read one photoresistor but I decided I would focus on light transmission first and come back to receiving light signals later.

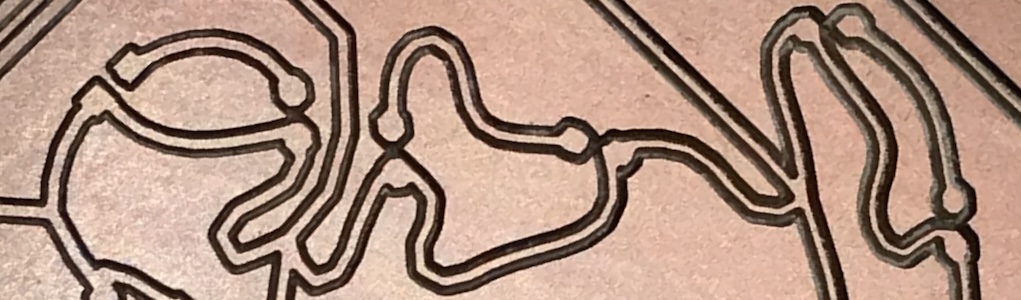

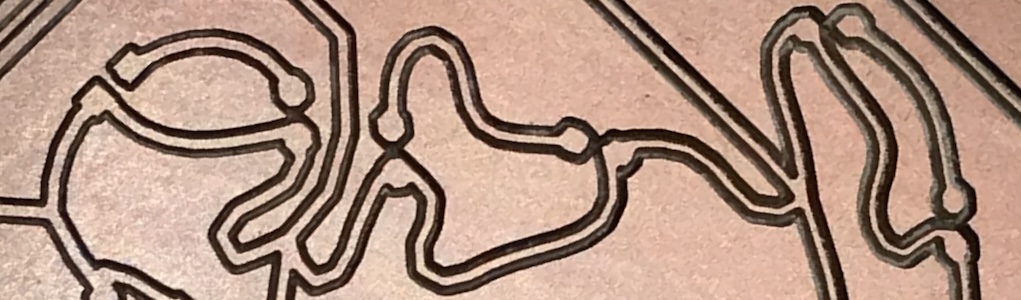

Now my plan was to get the circuit net into Houdini, do some simple force-directed iterative manipulation on it, and then get it back out as a PCB that I could fabricate. If I could come up with a reliable pipeline for that then I would have a way to organically randomize the PCB design for each inner face. I would just have to keep extending it after I went back and designed the full circuit which also included light reception.

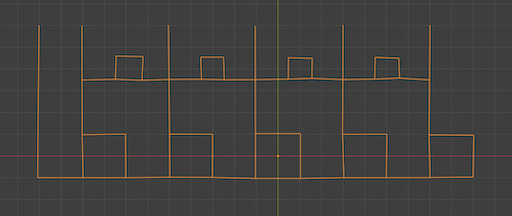

To import the circuit topology I laid it out as a mesh in Blender with each LED as a vertex and edges representing electrical connections.

In Houdini I adapted the same approach that I had used for the light guides. The basic idea is to lengthen the edges while creating new points if they get longer than a threshold distance. By combining that with forces to push the vertices apart and around you end up with a simple but very flexible generative growth system.

I fed the circuit topology into it and played around with the forces until I got some results that I liked. I attached some extra data to the vertices so I could keep track of which ones represented LEDs and which were added to grow the traces.

Then I wrote some Python code to transform the mesh into traces for KiCad. It’s easy to do this because the formats used by KiCad for schematics and PCBs are fairly well documented s-expressions. And you can just load them into your clipboard and then paste them directly into KiCad. I pasted the raw geometry in and then I added some traces to allow me to connect to it more easily for testing, as well as an outline with mounting holes.

I got an idea for generating the light guides differently that I wanted to try. Basically just some particle systems generating volumes and booleaned with fixed mating geometry created based on the locations of the LEDs.

Everything assembled together and lit up looked neat, but the light didn’t do what I was hoping it would in the resin. Shortly after I got sucked into a different project so this is where the chain of experiments ended.

Fast forward to 2023 and I was in batch at the Recurse Center and I found some activation energy to jump back into similar generative hardware systems design. I also wanted to get more fluent in Rust. So this time I looked more at tools I could use to prototype the software that would run on a distributed/amorphous computer like the light hive described above. I didn’t want to do purely abstract modeling, because at the end of the day I aspire to build beautiful artifacts in the real world. So I tried prototyping a semi-interactive design toolkit for myself which would let me use generative techniques to build up a virtual sculpture that could actually run code like the real instantiation would.

I love Houdini for prototyping procedural/generative systems so I decided I would just build some external parts that would plug into Houdini and reconfigure/reload themselves when changes were made to the design. I want the sculptures/artifacts to be interactive so I needed a GUI for interacting with the simulation. I ended up building that as a web app which used React Three Fiber to render the 3D model generated from Houdini and reload it when it changed. The Houdini scene annotated the geometry in a specific way so each individual part was labeled and could be updated to reflect changes to the state of the simulation. For example, a part could change color if its virtual LED lit up. And if I clicked on a part of the sculpture in the 3D scene that could generate a signal that would eventually reach a virtual input within the simulation so the virtual microcontrollers could react to it.

To simulate the virtual computer network I built a tool I called mycochip in Rust. I used simavr mainly because I’m nostalgic for the AVR architecture, it’s very simple, and I know it like the back of my hand. The network configuration (e.g. number, type, and connectivity of the nodes) could be defined using YAML generated from the Houdini scene. Inputs and outputs from the simulated AVRs could be streamed over sockets in Protocol Buffer messages.

A Node.js server hosted the web app, connected to the running mycochip simulation, and watched for updates to any of the scene files like the 3D models. Clicking on a part of the sculpture connected to a sensor in the browser would cause an event to get sent to Node.js over a WebSocket and then on to the relevant microcontroller running in mycochip. Real AVR code could then react to the input and send messages to other connected AVRs. The state of any connected outputs on the AVRs would be synced back out to the web app.

If you would like to see it in action then take a look at the YouTube video embedded above.

I made this prototype sculpture in a few hours as a quick demo but I ended up liking the way it turned out. The way I imagine it, the central stalks would be made of glass. The real imaginary system would be buried under the ground with just the tips of these stalks poking out to see the sky. I had the 10k year Long Now Foundation Clock design in mind while working on it. The glass stalks would concentrate light and carry it down to buried clusters of computers so the virtual inhabitants could observe the sky or maybe receive communications from orbiting colonies.

The way it is built up in Houdini is as follows:

In the video you can see how the system can be easily adjusted after it’s set up to try out different arrangements or entirely different ideas.